The falling cat problem is a problem that consists of explaining the underlying physics behind the observation of the cat righting reflex: that is, how a free-falling body (a cat) can change its orientation such that it is able to right itself as it falls to land on its feet, irrespective of its initial orientation, and without violating the law of conservation of angular momentum.

Although amusing and trivial to pose, the solution of the problem is not as straightforward as its statement would suggest. The apparent contradiction with the law of conservation of angular momentum is resolved because the cat is not a rigid body, but instead is permitted to change its shape during the fall owing to the cat's flexible backbone and non-functional collar-bone. The behavior of the cat is thus typical of the mechanics of deformable bodies.

Several explanations have been proposed for this phenomenon since the late 19th century:

Cats rely on conservation of angular momentum. (Marey 1894a, pp. 714–717)

The rotation angle of the front body is larger than that of the rear body. (McDonald 1955, pp. 34–35)

The dynamics of the falling cat have been explained using the Udwadia–Kalaba equation. (Zhen et al. 2014, pp. 2237–2250)

History

The falling cat problem has elicited interest from famous scientists including George Gabriel Stokes, James Clerk Maxwell, and Étienne-Jules Marey. In a letter to his wife, Katherine Mary Clerk Maxwell, Maxwell wrote, "There is a tradition in Trinity that when I was here I discovered a method of throwing a cat so as not to light on its feet, and that I used to throw cats out of windows. I had to explain that the proper object of research was to find how quick the cat would turn round, and that the proper method was to let the cat drop on a table or bed from about two inches, and that even then the cat lights on her feet." (Campbell & Garnett 1999, p. 499)

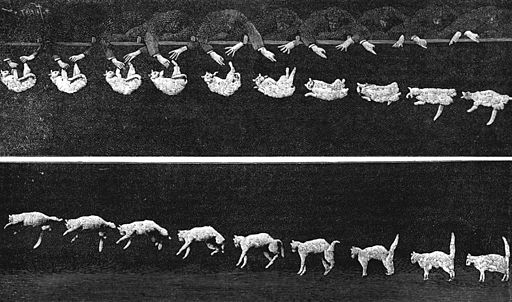

Whereas the cat-falling problem was regarded as a mere curiosity by Maxwell, Stokes, and others, a more rigorous study of the problem was conducted by Étienne-Jules Marey who applied chronophotography to capture the cat's descent on film using a chronophotographic gun. The gun, capable of capturing 12 frames per second, produced images from which Marey deduced that, as the cat had no rotational motion at the start of its descent, the cat was not "cheating" by using the cat handler's hand as a fulcrum. This in itself posed a problem as it implied that it was possible for a body in free fall to acquire angular momentum. Marey also showed that air resistance played no role in facilitating the righting of the cat's body.

Falling Cat – images which appeared in the journal Nature in 1894, captured by a chronophotographic gun, a device of Marey's own invention. The editor of Nature wrote, "The expression of offended dignity shown by the cat at the end of the first series indicates a want of interest in scientific investigation."

His investigations were subsequently published in Comptes Rendus (Marey 1894b, pp. 714–717), and a summary of his findings were published in the journal Nature (Nature 1894, pp. 80–81). The article's summary in Nature appeared thus:

M. Marey thinks that it is the inertia of its own mass that the cat uses to right itself. The torsion couple which produces the action of the muscles of the vertebra acts at first on the forelegs which have a very small motion of inertia on account of the front feet being foreshortened and pressed against the neck. The hind legs, however, being stretched out and almost perpendicular to the axis of the body, possesses a moment of inertia which opposes motion in the opposite direction to that which the torsion couple tends to produce. In the second phase of the action, the attitude of the feet is reversed, and it is the inertia of the forepart that furnishes a fulcrum for the rotation of the rear.

Despite the publication of the images, many physicists at the time maintained that the cat was still "cheating" by using the handler's hand from its starting position to right itself, as the cat's motion would otherwise seem to imply a rigid body acquiring angular momentum (McDonald 1960).

Solution

The solution of the problem, originally due to Kane & Scher (1969), models the cat as a pair of cylinders (the front and back halves of the cat) capable of changing their relative orientations Montgomery (1993). later described the Kane–Scher model in terms of a connection in the configuration space that encapsulates the relative motions of the two parts of the cat permitted by the physics. Framed in this way, the dynamics of the falling cat problem is a prototypical example of a nonholonomic system (Batterman 2003), the study of which is among the central preoccupations of control theory. A solution of the falling cat problem is a curve in the configuration space that is horizontal with respect to the connection (that is, it is admissible by the physics) with prescribed initial and final configurations. Finding an optimal solution is an example of optimal motion planning (Arabyan & Tsai 1998; Ge & Chen 2007).

In the language of physics, Montgomery's connection is a certain Yang-Mills field on the configuration space, and is a special case of a more general approach to the dynamics of deformable bodies as represented by gauge fields (Montgomery 1993; Batterman 2003), following the work of Shapere & Wilczek (1987).

See also

Parallel parking problem

Momentum wheel

Works cited

Arabyan, A; Tsai, D. (1998), "A distributed control model for the air-righting reflex of a cat", Biological Cybernetics, 79 (5): 393–401, doi:10.1007/s004220050488, PMID 9851020.

Batterman, R (2003), "Falling cats, parallel parking, and polarized light" (PDF), Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 34 (4): 527–557, Bibcode:2003SHPMP..34..527B, doi:10.1016/s1355-2198(03)00062-5.

Campbell, Lewis; Garnett, William (1 January 1999). The Life of James Clerk Maxwell. Macmillan and Company. p. 499. ISBN 978-140216137-7.

Ge, Xin-sheng; Chen, Li-qun (2007), "Optimal control of nonholonomic motion planning for a free-falling cat", Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, 28 (5): 601–607(7), doi:10.1007/s10483-007-0505-z.

Kane, T R; Scher, M P. (1969), "A dynamical explanation of the falling cat phenomenon", Int J Solids Structures, 5 (7): 663–670, doi:10.1016/0020-7683(69)90086-9.

Marey, E.-J. (1894a). "Mecanique animale: Des mouvements que certains animaux exécutent pour retomber sur leurs pieds, lorsqu'ils sont précipités d'un lieu élevé". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 119 (18): 714–717 – via Internet Archive.

Marey, É.J (1894b). "Des mouvements que certains animaux exécutent pour retomber sur leurs pieds, lorsqu'ils sont précipités d'un lieu élevé". La Nature (in French). 119: 714–717.

McDonald, D.A. (1955). "How does a falling cat turn over". American Journal of Physiology (129): 34–35.

McDonald, Donald (30 June 1960). "How does a cat fall on its feet?". New Scientist.

Montgomery, R. (1993), "Gauge Theory of the Falling Cat", in Enos, M.J. (ed.), Dynamics and Control of Mechanical Systems (PDF), American Mathematical Society, pp. 193–218.

"Photographs of a tumbling cat". Nature. 51 (1308): 80–81. 1894. Bibcode:1894Natur..51...80.. doi:10.1038/051080a0.

Shapere, Alfred; Wilczek, Frank (1987), "Self-Propulsion at Low Reynolds Number", Physical Review Letters, 58 (20): 2051–2054, Bibcode:1987PhRvL..58.2051S, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.2051, PMID 10034637, archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

Zhen, S.; Huang, K.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.H. (2014). "Why can a free-falling cat always manage to land safely on its feet?". Nonlinear Dynamics. 79 (4): 2237–2250. doi:10.1007/s11071-014-1741-2. S2CID 120984496.

Further reading

Richard Montgomery's homepage

Lagrangian Reduction and the Falling Cat Theorem

Hellenica World - Scientific Library

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License