Transfinite induction is an extension of mathematical induction to well-ordered sets, for example to sets of ordinal numbers or cardinal numbers.

Induction by cases

Let \( P(\alpha ) \) be a property defined for all ordinals \( \alpha \) . Suppose that whenever \( {\displaystyle P(\beta )} \) is true for all \( \beta <\alpha \) , then \( P(\alpha ) \) is also true.[1] Then transfinite induction tells us that P is true for all ordinals.

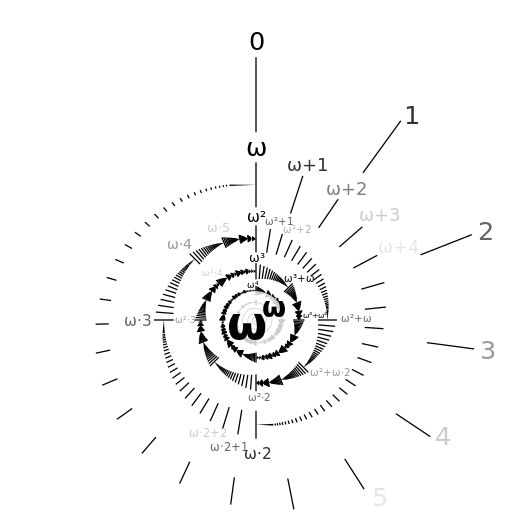

Representation of the ordinal numbers up to \( \omega^{\omega} \). Each turn of the spiral represents one power of \( \omega \). Transfinite induction requires proving a base case (used for 0), a successor case (used for those ordinals which have a predecessor), and a limit case (used for ordinals which don't have a predecessor).

Usually the proof is broken down into three cases:

Zero case: Prove that P(0) is true.

Successor case: Prove that for any successor ordinal \( \alpha +1 \),\( {\displaystyle P(\alpha +1)} \) follows from \( P(\alpha ) \) (and, if necessary, \( {\displaystyle P(\beta )} \) for all\( \beta <\alpha \) ).

Limit case: Prove that for any limit ordinal \( \lambda \) , \( P(\lambda)\) follows from \( {\displaystyle P(\beta )} \) for all \( {\displaystyle \beta <\lambda } \).

All three cases are identical except for the type of ordinal considered. They do not formally need to be considered separately, but in practice the proofs are typically so different as to require separate presentations. Zero is sometimes considered a limit ordinal and then may sometimes be treated in proofs in the same case as limit ordinals.

Transfinite recursion

Transfinite recursion is similar to transfinite induction; however, instead of proving that something holds for all ordinal numbers, we construct a sequence of objects, one for each ordinal.

As an example, a basis for a (possibly infinite-dimensional) vector space can be created by choosing a vector \( v_{0} \) and for each ordinal α choosing a vector that is not in the span of the vectors \( {\displaystyle \{v_{\beta }\mid \beta <\alpha \}} \). This process stops when no vector can be chosen.

More formally, we can state the Transfinite Recursion Theorem as follows:

Transfinite Recursion Theorem (version 1). Given a class function[2] G: V → V (where V is the class of all sets), there exists a unique transfinite sequence F: Ord → V (where Ord is the class of all ordinals) such that

F(α) = G(F ↾ {\displaystyle \upharpoonright } \upharpoonright α) for all ordinals α, where \( \upharpoonright \) denotes the restriction of F's domain to ordinals < α.

As in the case of induction, we may treat different types of ordinals separately: another formulation of transfinite recursion is the following:

Transfinite Recursion Theorem (version 2). Given a set g1, and class functions G2, G3, there exists a unique function F: Ord → V such that

F(0) = g1,

F(α + 1) = G2(F(α)), for all α ∈ Ord,

F(λ) = G3(F \( \upharpoonright \) λ), for all limit λ ≠ 0.

Note that we require the domains of G2, G3 to be broad enough to make the above properties meaningful. The uniqueness of the sequence satisfying these properties can be proved using transfinite induction.

More generally, one can define objects by transfinite recursion on any well-founded relation R. (R need not even be a set; it can be a proper class, provided it is a set-like relation; i.e. for any x, the collection of all y such that yRx is a set.)

Relationship to the axiom of choice

Proofs or constructions using induction and recursion often use the axiom of choice to produce a well-ordered relation that can be treated by transfinite induction. However, if the relation in question is already well-ordered, one can often use transfinite induction without invoking the axiom of choice.[3] For example, many results about Borel sets are proved by transfinite induction on the ordinal rank of the set; these ranks are already well-ordered, so the axiom of choice is not needed to well-order them.

The following construction of the Vitali set shows one way that the axiom of choice can be used in a proof by transfinite induction:

First, well-order the real numbers (this is where the axiom of choice enters via the well-ordering theorem), giving a sequence \( \langle r_{\alpha }|\alpha <\beta \rangle \) , where β is an ordinal with the cardinality of the continuum. Let v0 equal r0. Then let v1 equal rα1, where α1 is least such that rα1 − v0 is not a rational number. Continue; at each step use the least real from the r sequence that does not have a rational difference with any element thus far constructed in the v sequence. Continue until all the reals in the r sequence are exhausted. The final v sequence will enumerate the Vitali set.

The above argument uses the axiom of choice in an essential way at the very beginning, in order to well-order the reals. After that step, the axiom of choice is not used again.

Other uses of the axiom of choice are more subtle. For example, a construction by transfinite recursion frequently will not specify a unique value for Aα+1, given the sequence up to α, but will specify only a condition that Aα+1 must satisfy, and argue that there is at least one set satisfying this condition. If it is not possible to define a unique example of such a set at each stage, then it may be necessary to invoke (some form of) the axiom of choice to select one such at each step. For inductions and recursions of countable length, the weaker axiom of dependent choice is sufficient. Because there are models of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory of interest to set theorists that satisfy the axiom of dependent choice but not the full axiom of choice, the knowledge that a particular proof only requires dependent choice can be useful.

See also

Mathematical induction

∈-induction

Transfinite number

Well-founded induction

Zorn's lemma

Notes

It is not necessary here to assume separately that P(0) is true. As there is no \( \beta \)less than 0, it is vacuously true that for all \( {\displaystyle \beta <0} \), \( {\displaystyle P(\beta )} \)is true.

A class function is a rule (specifically, a logical formula) assigning each element in the lefthand class to an element in the righthand class. It is not a function because its domain and codomain are not sets.

In fact, the domain of the relation does not even need to be a set. It can be a proper class, provided that the relation R is set-like: for any x, the collection of all y such that y R x must be a set.

References

Suppes, Patrick (1972), "Section 7.1", Axiomatic set theory, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-61630-4

Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics

Graduate Studies in Mathematics

Hellenica World - Scientific Library

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License